It's too expensive! Let's make it more expensive!

Labour's diagnosis of British education hasn't changed since Corbyn; that's why their prescription will only make matters worse. Market structure analysis tells us to do....anything but this!

Summer 2017 was the “OOOOOH Jeremy Corbyn” phase. Regarding Corbynomics, I remember reading something like:

You go to Dr Corbyn and he correctly diagnoses you are severely ill. Sad news.

You have a heart complaint. Dr Corbyn wrongly diagnoses cancer. In your liver. And he prescribes the amputation of your left leg. Now you’re an amputee, needlessly worrying about your liver, and needing heart treatment you don’t know about. Worse news.

There was (is) an inequality problem in the UK. Sad. It was (is, QED, 2024) fatal for the Conservative Party not to grasp it, for example by doing something about housing and rolling back QE-induced inflation of asset prices. But one-trick pony Corbyn offered only the wrong diagnosis (boo-hiss capitalism) and the wrong remedy (yay, redistribution). Worse.

Bridget Phillipson hasn’t budged an inch from Corbyn on Education. She’s sticking with a diagnosis of “independent schools are the problem” and a remedy of “anything that harms independent education will help”. As I wrote here , Bridget Phillipson is guided by entirely inaccurate stereotypes about rich people in gold-plated schools. However, regarding some of the more expensive schools, she is quoted here, and she has a point:

“Over the last decade or more, private school fees have gone up above and beyond inflation year upon year. And that means that increasingly, middle class parents are priced out of private schools.”

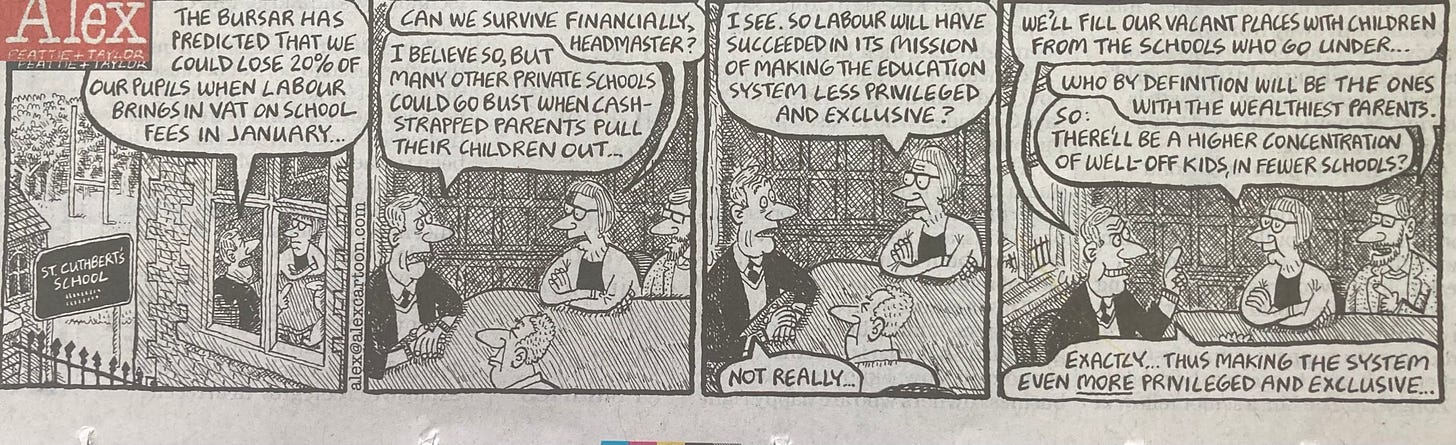

But she doesn’t understand why. Then she declares the expensive thing should be more expensive, and never mind that she’s making the situation worse on exactly the “middle-class access / social mobility” concerns she claims to value. She should read Alex in the Daily Telegraph:

This post proposes a better approach, starting from a market analysis that any strategy consultant or A-level economist should recognise. This is important because (1) it’s yet another thing the “independent” IFS should have considered, but didn’t (2) it helps us towards what we should do instead.

Diagnosis: the 93pc

freetaxpayer-funded monopolist shapes the nature of competition in the independent sector. Obviously. These schools have to compete against “free” via differentiation, trust, premium service and finding a niche. Market structure tells us why they don’t compete on price.Remedy: Corbyn’s Tax hinders choice and competition between state and independent, and between independent schools. It will make the complaints of “exclusive, expensive” even worse.

Instead: we need supply-side remedies to enhance choice and competition in the independent sector, encouraging more people to make the pro-social, taxpayer-saving choice of independent school.

Market structure

Here’s what the CMA, or any competition regulator would argue (or should argue, if you assume they’re a pro-market, pro-customer regulator, not a statist quango increasingly obsessed with social welfare yuck). You can’t understand rugby without learning the rules. You can’t analyse a horse race without looking at the distance and the ground. You can’t comment on price and competition in a market without looking at market structure.

The CMA should say a well-functioning market is one where customers, by exercising choice, have a good chance of improving their outcomes, and providers have an incentive to respond to those choices. In contrast:

Education is dominated by a 93% price-fixing monopolist that benefits from strong institutional protections: a captive mandated customer base, taxpayer funding even from those customers that make other arrangements, bans on top-up funding, caps on admissions for successful schools, economic protections for struggling schools;

It’s no surprise that:

a 93% monopolist delivering patchy outcomes drives certain behaviours among households:

customers of limited means struggle to exercise choice, and the current Government seems keen to make it harder for them;

customers with means either game the monopolist’s rules by finding pockets of excellence and paying for value-add (catchment areas, tutoring towards grammar schools, 7-figure PTAs claiming gift aid);

other customers with means escape the monopolist’s provision (by paying for independent school);

the vestigial 7% “market” is likely to struggle to fulfil mid-market, cost-conscious demand (think VW) and is likely to lead to non-price competition (Mercedes/Rolls-Royce/Porsche/Range Rover);

The independent school market has intrinsic features (information challenges, high entry costs, high switching costs and severe political risk) that discourage entry and hinder price competition; the nature and conduct of the 93% monopolist makes it much worse;

Corbyn’s tax increases the cost of “escape” and forces more parents to choose “game” thus ensuring (per the ever-accurate Alex cartoon above) less competition, more expense, more exclusivity in the vestigial “market”; more pressure on what’s good in the state sector, and less social mobility;

To improve quality, diversity and choice, with the effect of giving more middle-class parents the affordable opportunities and social mobility Labour say they care about, we instead need supply-side policies that are pro-choice, pro-supply and pro-competition.

Because their whole thought process is bonkers, Labour instead land on a remedy that’s bonkers, will do nothing to fix the troublesome outcomes, and will make some of them worse.

For the sake of argument I’m deliberately ignoring other upward pressures on fees that have affected schools, and independent schools in particular in the last decade or so. Also, arguably, school governors could have voluntarily applied more cost discipline instead of over-investing in ways that weren’t always in the interests of families.

The point here is that the market failed to make governors apply cost discipline, not because (as the IFS paper hints) parents are delighted about the rising fees and the exclusivity game, but because of market structure hindering competition. It wasn’t possible for families to impose cost discipline and secure better outcomes.

I’m trying to explain how market structure and government intervention contribute to those pressures, so that we can understand how Corbyn’s Tax makes them worse.

I asked ChatGPT

I asked ChatGPT to analyse a market with a state-funded 93% monopolist “free at point of delivery”, with information challenges, long-term relationships and high switching costs. You can read the full question and answer by clicking this link (I think it’ll work, please let me know). Chat GPT told me almost exactly what I’ve written above:

Since the monopolist offers a "free" service (at least at the point of delivery), smaller firms cannot compete on price.

Due to its dominant position and the lack of competitive pressure, the monopolist may suffer from issues of complacency or inefficiency

Public accountability might enforce a baseline quality level, but this is often focused on maintaining minimum service standards rather than excelling in customer satisfaction or innovation

There is a lack of price competition between the niche/premium providers. But it’s not price-inelastic because, as the IFS assumes, parents are blissfully happy paying huge fees and have bottomless pockets. It’s price-inelastic because the free taxpayer-funded monopolist attracts all the cost-conscious customers and provides a dodgy / variable service, leaving a sector that is too small for price competition to happen at all. Because that’s what monopolists do.

Choice is good

The CMA would say, if you asked them…..well, they should say, something like this:

We need more private schools | Frank Young | The Critic Magazine

“we badly need disrupters challenging orthodoxy and allowing parents to judge what makes for a good education. It’s fundamentally a question of where power lies. Making life harder for private schools might make for a good stump speech, but it is not the iconoclastic approach to education that would disrupt and challenge established thinking.”

The point here, and if Our Bridget ever spoke to a single independent school or one of their families (or a sensible economist), she’d learn: not everyone paying through the nose is thrilled about the Rolls-Royce-level tariffs. Many would love to be able to buy a Volvo or VW education instead, a good school without bells and whistles, that caters for middle class parents and allows them a holiday or two without selling body parts. Many, looking beyond their own circle, (including yours truly) would also love more families to have access to independent school, via more schools at more affordable price-points. And many would like to choose something a bit different, like a democratic or Steiner school.

Why can’t they? Those Volvo or VW schools don’t exist, unfortunately, in most of the country. Those mid-market offerings are few and far between. Why? Because the free taxpayer-funded outfits “crowd them out” - it’s just too difficult for a Volvo to compete against a Ford, if the Ford is being given away. (I’m not deliberately maligning a Ford. I like Fords).

Even if the Ford needs a service and has 100,000 miles, then for “free” it’s still worth a look. Cost-conscious or budget-constrained customers look no further. These are your standard comprehensives and academies.

If the Ford’s in good nick, or brand new, then for “free” it’s a terrific deal and hotly contested. Even pretty wealthy customers will queue at the door. These are your catchment areas and grammars.

To get beyond “free” the offering has to be really, really good (and that can make it expensive) or really, really different (and that can make it niche). For these reasons it’s not a huge market, because there aren’t that many well-off or niche people. So the sheer size of the market isn’t that great and there isn’t a huge number of independent schools. So competition, at the local level (and day school is by definition at the local level, boarding schools obviously less so) can be limited.

If only we could encourage choice and social mobility.

The Education Tax hinders choice and social mobility

Apart from the revenue argument, that the tax will raise £1.5bn (it probably won’t) and won’t harm any children (it will)… the Education Tax has unfortunate effects on the market. The institutionally-advantaged 93% monopolist “crowds out” a chunk of mid-market supply simply by being “free”, and now the Education Tax makes the advantage worse. Now it will be even harder to sell something “just a bit” better than a state school, or cater to a family preference like a Steiner School.

Here’s just a few implications, all of which are terrible for social mobility:

The independent sector will, as the Alex cartoon says, become smaller and more exclusive, even less attainable for a middle-class family. The super-rich, of course, will be fine.

Via school contractions, closures, and mergers, the sector will, locally, become even less internally competitive, and parents even less able to make comparisons, switch, and force competition on price. Parents and governors with a preference for going even further upmarket will have even fewer cost-conscious parents holding them back.

The sector will be less able to offer bursaries and partnerships.

Given there is no intention of growing popular state schools, in fact Labour want to “take back control” of admissions for all maintained schools rather than allow the good ones to expand and the rubbish ones to wither, the catchment area premium and grammar school contests will become even more intense (more demand for the same supply); as noted here by a comprehensive teacher “the refugees from the private sector will inevitably take places from less privileged children at the best comprehensives. The only way to remedy this would be to create additional places at outstanding state schools, but the Government has no intention of doing that”; and as reported here this is already happening.

Commentators’ failure to consider how market structure defines price and performance, while complaining vigorously about both, illustrates the intellectual vacuum in this Government’s education project.

So Phillipson complains about segregated education, and pricing-out the middle-classes, and exclusivity. She has chosen the perfect flagship policy…to make these concerns worse.

For future discussion: what are the education policies that could instead encourage more competition and make independent education more accessible?

Obviously, offering parents a voucher towards the cost of their children’s education would be a good way of increasing parental choice and expanding the offerings available. To be redeemed in a state school at no extra cost, or a private one at variable extra cost depending on the bells & whistles offered.